Title:

A Christmas Carol

Format:

Live television drama

Country:

UK

Production company:

BBC Television

Year:

1950 – broadcast twice, both as live performances by the same

cast; first at 9pm on Christmas Day, and then again in the

For the Children

slot at 5pm on Wednesday the 27

th.

Length:

Approximately 90 minutes. That was the scheduled slot,

although live dramas could occasionally over- or underrun – but the evidence

suggests this ran pretty much to time, as there’s no mention of anything to the

contrary in the BBC’s audience research report.

Setting:

Victorian

Background:

For the second time,

Bransby Williams was due to bring to the television screen his performance as Scrooge, which had become well-known on stage throughout much

of the 20

th century to this point. And

unlike

his scheduled one-man performance from 1936, this time it did actually

happen – but sadly, once again we are unable to see it now.

That one wasn’t really a ‘Lost Carol’ as it never

actually happened in the first place, and it could also be argued that this one

isn’t strictly-speaking ‘lost’ either. It never ‘existed’ to be lost at all,

in a recorded sense, any more than a stage play does. It was performed live,

twice, and on neither occasion was any effort made to preserve it for posterity.

It simply went out into the ether, seen only by those in Britain who had

television sets switched-on at the time, and was then gone forever.

And yes, it would have been seen by anybody who had a

television set switched on – because at this point the BBC was still the only British

television broadcaster. Their single channel was now being beamed out from two

transmitters, at Alexandra Palace serving London and the surrounding area, and

at Sutton Coldfield serving the English Midlands.

There were, however, now hundreds of thousands of

television viewers, with the number increasing all the time. Television was

still a way from being a mass medium at this point, but nor was it any longer the luxury

of a tiny few.

The live performance, pretty much universal for all British television drama of the time, meant that, yes, the entire cast and crew were there on Christmas Day.

It was also common for there to be a second performance, in this case just two

days later, put out this time in the 5pm children’s slot so that younger

viewers who had not had the chance to watch it first time around would be able

to see it.

|

| Bransby Williams appearing on television in 1957 |

All, however, did not go entirely well for Williams in

this second performance. Having been forced to cancel his planned 1936

television debut at Scrooge due to illness, the second performance of this

full-cast version almost went the same way. On New Year’s Day, the

Daily

Herald reported how Williams had become ill early during the December 27

transmission, and that he was “in agony for one and a half hours before the

cameras.”

“I had hardly given my first bellow of rage before I was

gripped by the most awful abdominal pains,” he was quoted as having told the

paper. “My training prevented the viewers – in Children’s Hour – from knowing

anything was wrong. They just saw my face working more than usual. The play ran

according to script.” The

Herald further added that “the contortions of

his face through pain made Scrooge’s rage all the more frightening,” and that

Williams had “refused to abandon his part, because there was no understudy.”

Several of the newspaper previews and reviews of the

production mention how it took up the use of two television studios, rather

than simply being done in one as was more usual – although it was not unknown

for big productions to be spread across a pair. The

Birmingham Post, in

a preview on December 14, claimed that “Bransby Williams, in the part of

Scrooge, will be working on one set, while the rest of the cast will be

performing elsewhere, and the two pictures will be superimposed to give a

suitably ghostly effect.”

While this was true for certain scenes, it gives the

impression that Williams was alone in one studio and the rest of the cast in

the other, which was not the case. Only the scenes with the ghosts were done

separately in this manner, and not necessarily always in different studios, so

that the two could be cross-faded. However, it’s still impressive that Williams

and his co-stars were able to play effectively without having one another

nearby, whether they were in the same studio at the time or not.

“There are about fourteen scenes,” the

Huddersfield

Examiner reported on the 20

th. “And approximately half the

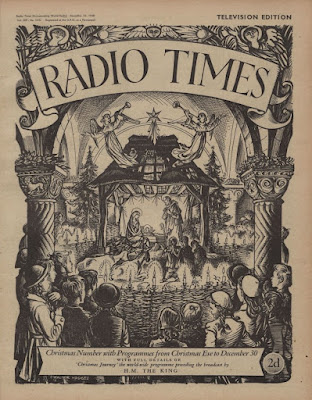

performance will be superimposed to give a suitably ghostly effect.” Producer

Eric Fawcett had commented on the difficulties this presented in

a preview in

the Christmas edition of the Radio Times. “We are trying to keep the

ghosts as ghostly as possible,” he told the magazine, “even though this entails

the actors playing scenes while standing yards apart. Two-studio production

will necessitate such careful work on the part of the cameramen, sound and

vision-mixers and engineers – to say nothing of those dyed-in-the-wool enthusiasts,

the studio staff.”

As to

which studios these were, I have no hard

evidence but I would say almost certainly the two original BBC Television

studios, Studios A and B at Alexandra Palace in North London. The BBC had in 1950 begun

using their newly-acquired facility at Lime Grove, a set of ex-film studios, with Studio D having launched at the children’s studio in May.

Studio G had been opened for television with a variety spectacular on the

Saturday before Christmas, but at this point drama production still seems to

have been based at the Palace so it seems almost certain that

A Christmas

Carol came from there.

|

| Alexandra Palace in 1946, with the transmitter mast above the BBC-occupied wing |

Cast and Crew:

I wrote about Bransby Williams’s background playing

Scrooge in

my piece on the abandoned 1936 production, so there’s little need to

repeat that here. It is worth saying, however, that at the age of 80 he must

surely have been one of the earliest-born people ever to have starred in a

television drama.

He did, however, have some level of assistance –

The

Stage the following month mentioned “

Ewart Wheeler, who doubled so

ingeniously for Bransby Williams in the recent televising of

A Christmas

Carol.” Wheeler is

credited in the Radio Times simply for ‘other

parts’, so you can imagine how he perhaps played Scrooge for certain shots seen

only from behind, while Williams was prepared for a following shot or scene.

Among the rest of the cast, one name which leaps out to

anyone familiar with the BBC’s 1950s television output is that of

Patricia Fryer as ‘Fanny’ – Fryer would later play Margaret Appleyard, youngest of the

Appleyard siblings in the BBC’s children’s soap opera-cum-sitcom

The

Appleyards, taking over the part for the second series in 1953 before

outgrowing it herself in 1955, and returning for the one-off

Christmas with

The Appleyards in 1960. There is no Fan listed in the cast, so ‘Fanny’ is

presumably a slightly-renamed version of Scrooge’s sister from the Christmas

Past scenes, which Fryer would have been the right age for.

As is not exactly common but also not unique, the three

performers playing the ghosts here double-up in other parts.

Arthur Hambling as

the Spirit of Christmas Past also appears as one of the stock exchange

gentlemen discussing Scrooge’s death in the Yet-to-Come scenes;

Julian d’Albie

as the Ghost of Christmas Present – yes, they were billed as a mix of ‘Spirit’

and ‘Ghost’ – is also credited as a ‘portly gentleman’, and

WE Holloway as the

Spirit of Christmas to Come (no ‘yet’ in the billing) also portrays Marley.

Whether this was for effect or for economy is debateable,

however it appears to have almost certainly been the former. ‘Young Scrooge’ actor

John Bentley also has a credit as a night watchman appearing early on in the

play, and similarly Old Joe actor

Leonard Sharp appears as a crossing

sweeper. Fryer too had a second role, credited as ‘Girl waif’ alongside

Michael Edmonds as ‘Boy waif’ – from their placing in the order-of-appearance cast

list, almost certainly these are Ignorance and Want from the end of the

‘Present’ section. This perhaps adds weight to the idea that the doubling-up

was a deliberate effect, with some of the figures Scrooge encounters through

the story having the faces of those who are familiar to him.

On the subject of familiar faces, several of the cast were old co-stars of

Williams’ – he remarked to the

Daily Herald after his illness during the

second performance that “there was always one of my old pals – Jimmy d’Albie,

Bill Holloway or Arthur Hambling – waiting to give me an arm. Once or twice

they half carried me.”

Kathleen Saintsbury, who played Mrs Cratchit, was also a

friend and regular co-star from the stage, who would appear on Williams’s

This

is Your Life in 1958.

|

| Kathleen Saintsbury appears on Bransby Williams' episode of This is Your Life in 1958 |

Perhaps one of the most notable names in the cast is

Barbara Murray, as Belle – evidently not named here, as she’s only given as ‘fiancée’

in the cast list in the

Radio Times. Murray was already a recognisable

face from British films at this point, having co-starred in

Passport to

Pimlico the previous year, and would continue to be a notable screen presence

in British cinema for some years to come. So it’s quite impressive that they

were able to drag her away from her Christmas dinner to come and do this –

although it is possible that her scene could perhaps have been a film insert,

especially as Murray is not one of those who doubles up in another role. Such

inserts

were being used in television drama by this point, although only very

sparingly and more often than not for outdoor and action sequences rather than

dialogue scenes.

It was also the usual practice of BBC television drama at

the time for there to be a single person credited as ‘producer’ who performed

what might today be understood to be the functions of both producer and

director – overseeing the production both administratively and creatively. This

was the case here, with producer

Eric Fawcett also having written the

adaptation – although from an existing stage play version by

Dominic Roche,

rather than directly from the book. Fawcett had a long career with BBC Television,

beginning as a producer on the pre-war service from Alexandra Palace in the

1930s and continuing right through until the 1970s as a drama director.

As a

Doctor Who fan and someone

with a great interest in the creation of that programme, I cannot resist noting the presence

of

James Bould as the designer. Thirteen years later, Bould would be the BBC’s

Design Department Manager and one of those who was not keen about

Doctor Who

going ahead as he didn’t think his department had the time, manpower and

resources to provide for its needs. He was presumably having a happier time here with a different story which went through the barriers of time.

Underdone Potato:

Without having had access to the script, it’s obviously

very difficult to say anything much for certain about the specific elements of

this version. However, with the cast listed in order of appearance in the

Radio

Times, we do know that Julian d’Albie, Leonard Sharp and John Bentley,

later to appear as the Ghost of Christmas Present, Old Joe and Young Scrooge

respectively, all appear early on, after only Williams as Scrooge,

John Ruddock

as Bob Cratchit and

Robert Cawdron as Fred, so there seems to have been a

deliberate level of foreshadowing there.

I have been able to read the BBC’s audience research

report on the production, which notes how “There was praise… for the way the

atmosphere of mid-Victorian London was suggested, especially in the opening

scenes ‘which set the mood for the whole play’.”

Past:

The credits for

Sean Lynch as ‘Boy Scrooge’ and John

Bentley as ‘Young Scrooge’, as well as Patricia Fryer as ‘Fanny’ and Barbara

Murray as ‘Fiancée’, indicate that we get the usual scenes of Scrooge as an

unhappy schoolboy, and later breaking his engagement – or rather, having it

broken.

There is, however, no credit for anyone playing Fezziwig,

which suggests that the party scene was either omitted or scaled-down. There is

a production credit for “Dances arranged by John Armstrong”, which would surely

have been mostly likely to have been for a Fezziwig scene. Perhaps it was only

briefly shown using extras.

Present:

Again, we can mostly only try and guess at what was shown

from the cast list – but we certainly have the scene with the Cratchits, as

there are credits for Mrs Cratchit, Martha, Peter, Tim and unnamed ‘boy’ and

‘girl’ Cratchits. Fred was already credited for his earlier appearance at

Scrooge’s office, so it’s uncertain whether there was a scene at his Christmas

lunch. I am inclined to think not, as there is a credit for ‘Ann Wriggs’ – seemingly an error, and meant to be

Ann Wrigg without the ‘s’ – as ‘Mrs

Fred’ but not until the very end – suggesting she is not seen until Scrooge

visits after his redemption to go and make amends.

Yet to Come:

There are credits for the gentlemen who discuss Scrooge’s

death, and for Joe and Mrs Dilber discussing the sale of his things, but with

the Cratchits having been credited earlier it’s impossible to know whether

their future scene was included here – but I suspect it probably was.

The unnamed reviewer, credited only as ‘Cathode’, in the

Wokingham

& Bracknell Times gives us an impression of how the Spirit was realised

for this section, and they were not particularly impressed. Having praised the

production generally, ‘Cathode’ felt that “the Ghost of Xmas Yet to Come looked

too much like a member of the Ku-Klux-Klan.”

What’s To-Day:

Again, because most characters who would normally

re-appear here have already been credited, it’s very difficult by this stage to

be able to determine too many specifics without the script. However, we can say

that there was

Tony Lyons as ‘Boy with the goose’, and as mentioned above there

does appear to have been a scene of Scrooge going to dine with his nephew as

Mrs Fred is the final new character credited as appearing. We do

know that Scrooge lifted up Tiny Tim at the end of the Christmas Day performance

– because the

Daily Herald noted Williams was unable to do so on the second

performance due to his illness.

Review:

Obviously I cannot review the production myself as I have

not seen it, and nor sadly will I ever be able to, and I have not currently

been able to read a copy of the script. However, fortunately unlike for some

lost versions of the

Carol we can get at least some impression of what

it was like, from contemporary reviews – both professional, and from ordinary

viewers.

The BBC at the time did not yet compile viewing figure as

such. They did, however, have a panel of several hundred families selected as

being a representative cross-section of the audience, who recorded their

reactions to the various programmes. From their responses, the BBC calculated

that some 59% of television sets had been switched on for

A Christmas Carol

on Christmas Day, with 23% for the repeat in

For the Children two days

later.

The first performance had an average of 4.35 people

watching per set in use, and the second performance 3.19. Both received very

good ‘Reaction Index’ figures – the indication of how much those in the sample

group who watched a programme had enjoyed it. The first performance had a score

of 74, and the second 73. This was, as the audience research report noted,

“well above the current average (63) for studio performances of plays.”

The report does also note, however, that “The audience

for this programme, though large by normal standards, was by no means

outstanding compared with others during the Xmas holiday period, large numbers

of ‘guest viewers’ leading to high ‘viewers per sets-in-use’ figures for nearly

all programmes.”

In terms of qualitative rather than quantitative feedback,

it’s fascinating that the audience research report records an almost reverent

attitude towards the

Carol. Noting that 94% of the 272 who completed

questionnaires related to the programme indicated that the story had already

been familiar to them, the report suggests that “because this story now ranks

as a Christmas tradition most viewers felt it to be beyond criticism.”

Not all, however. “A few admitted a slight feeling of

aversion for its ‘outdated’ sentimentality and insistence on a moral ‘which now

seems to have lost much of its original point’.” While there was “little

comment on individual points,” some viewers felt that “the length of the novel

made it a difficult subject for television and that some cutting, especially in

the scenes depicting Scrooge’s earlier life, would have done no harm.” Which

seems a strange thing to say given it’s quite a short book, and a 90-minute

slot ought to enable it to be done fairly well.

Williams’s performance as Scrooge was “widely regarded as

little short of perfect,” with some who had seen him play the part on stage in

the past “delighted to find he could still play it ‘with all the old zest’.”

John Ruddock as Cratchit, Thomas Moore as Tim and Robert Cawdron as Fred we

also “singled out as especially memorable.”

The production techniques seem to have gone down well,

also, with report stating that viewers “thought very well of the production and

settings, particularly of the camera-work and sets in the spirit scenes. As

several said, here the resources of television came into their own, enabling

the viewer to

see things which were quite impossible to manage on the

stage.”

Among the professional reviewers, George Campey in the

Evening

Standard admitted that “the attention of some of my guests wandered during

the first hour.” However, he himself “sat enthralled by the encounters between

Scrooge (played with veteran knowledge by Bransby Williams) and the assorted

spectres in a production which fully evoked the Dickensian spirit. This play

must have been a producer’s nightmare. Eric Fawcett, at the helm, handled the

tricks and the action with consummate skill.”

AE Jebbett in the

Evening Despatch liked

Williams’s “smooth melodrama” as Scrooge, but felt overall that the production

was too long. Cyril Butcher in

The Sketch’s round-up of Christmas

viewing had no such qualms, praising Eric Fawcett for having “turned in one of

the best jobs of work in his career. The story, with its ghosts and spirits,

obviously lends itself to a full use of camera superimposition – a dangerous

trick used by inexpert hands. But Mr Fawcett’s are just about as experienced as

one will find. Nor did he, in this welter of technicalities, forget that he was

dealing with a lovely and moving tale which needs most delicate handling. Thank

you, Mr Fawcett.”

‘Cathode’ in the

Wokingham & Bracknell Times

“had that queer feeling that one gets when one visits an entirely strange place

and feels ‘I have been here before.’ For everything in the play was just as I

had imagined it. The brilliant Scrooge by that Grand Old Man of the stage,

Bransby Williams, really made old Ebenezer live, and

Dorothy Summers gave an

excellent portrayal of Mrs Dilber.”

Apart from the aforementioned reservation about the

costume of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, the only criticism ‘Cathode’

made was that “the Ghost of Xmas Past was not nearly as awesome as it might

have been.”

In a Nutshell:

An important milestone in the

Carol’s television

history, it’s a shame we can’t see this today – but that’s nobody’s fault, it’s

simply the way things were. You may as well blame a stage play for ‘not

existing’.

Links:

IMDbRadio Times