Title:

A Christmas Carol

Format:

One-man performance with illustrations, on multi-camera studio video

Country:

UK

Production

company:

BBC Television

Year:

1982 (first broadcast on BBC Two in the UK from December 21st-24th that year)

Length:

4 episodes, each of approximately 15 minutes

Setting:

Victorian

Background:

Done in the style of the famous children’s series Jackanory, with an actor doing a performed reading of a condensed version of the story, these four short episodes roughly correspond with the first four ‘staves’ of the original story – with the fifth and final ‘stave’ added into the fourth episode. The episodes were originally – and, as far as I can tell, only – transmitted on BBC Two in the UK at 3.40pm on consecutive afternoons in the run-up to Christmas, from the 21st to the 24th of December 1982.

Presumably, given

its Jackanory style, it was designed as something to help keep the

children entertained in the afternoons once the schools had broken up for

Christmas, but it’s not an explicitly youth-orientated version of the story.

Perhaps that’s why, despite it being made by an experienced Jackanory

team, it didn’t go out under that programme’s umbrella – so that adults wouldn’t

be dissuaded from watching it thinking it was purely kids’ stuff.

It’s perhaps

fitting that the BBC made such a version, as their first ever television

adaptation of the Carol had been a one-person telling, starring Bransby

Williams – a well-known stage Scrooge – in 1936. Williams had again performed a one-man versions for BBC Television in 1952, the latter the earliest

British TV version to exist, being film recorded and regularly repeated for

several Christmases thereafter. Michael Horden also did a reading for the BBC, in three parts in 1963.

A Christmas Carol

One-man performance with illustrations, on multi-camera studio video

UK

BBC Television

1982 (first broadcast on BBC Two in the UK from December 21st-24th that year)

4 episodes, each of approximately 15 minutes

Victorian

Done in the style of the famous children’s series Jackanory, with an actor doing a performed reading of a condensed version of the story, these four short episodes roughly correspond with the first four ‘staves’ of the original story – with the fifth and final ‘stave’ added into the fourth episode. The episodes were originally – and, as far as I can tell, only – transmitted on BBC Two in the UK at 3.40pm on consecutive afternoons in the run-up to Christmas, from the 21st to the 24th of December 1982.

Cast and crew:

The Jackanory feel is very much confirmed by a look at the talent working on this behind-the-scenes. The adaptation was written by Janie Grace, who over the previous decade had written nearly 100 episodes of Jackanory – and had also directed for the series. Grace went on to have a stellar career as a producer and executive producer in British children’s television, becoming head of Nickelodeon in the UK in the mid-1990s and later head of Children’s ITV.

Director

Christine Secombe had also been a Jackanory regular, as well as helming

multiple episodes of a variety of hugely well-known and popular British

children’s TV shows, such as Grange Hill, Play School and Jonny

Briggs.

That this is a Jackanory

without the branding is perhaps finally sealed by the presence of Angela Beeching as producer. She had been producing Jackanory since the early

1970s and would continue to do so until towards its end in the mid-1990s,

overseeing many hundreds of editions of the programme.

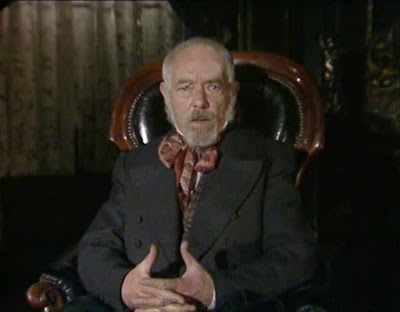

The reader is

actor Michael Bryant, who had form with BBC Two Christmas specials – ten years

earlier, he had played the lead in Nigel Kneale’s famous Christmas ghost story

for a modern era, The Stone Tape. He also had various supporting parts

in famous films to his name, such as one of the Titanic’s officers in A

Night to Remember, and Lenin in Nicholas and Alexandra. Bryant had

also done several readings for Jackanory down the years, as well as for

a 1980 series made by the Jackanory team called Spine Chillers,

which broadcast telling of ghost stories aimed at older children.

As was common

with Jackanory, Bryant’s reading is accompanied by

specially-commissioned illustrations. These were done by Paul Birbeck, another

regular contributor to Jackanory, who had also created the opening title

sequence for the BBC’s famous 1980s Miss Marple series, and the

backgrounds for the Glynis Barber Jane adaptations.

The Jackanory feel is very much confirmed by a look at the talent working on this behind-the-scenes. The adaptation was written by Janie Grace, who over the previous decade had written nearly 100 episodes of Jackanory – and had also directed for the series. Grace went on to have a stellar career as a producer and executive producer in British children’s television, becoming head of Nickelodeon in the UK in the mid-1990s and later head of Children’s ITV.

Underdone Potato:

Bryant doesn’t so much seem to represent Dickens as much as a generic Victorian gentleman and general omniscient narrator, although he does so from locations representing where Scrooge is at different parts of the story. This is most evident in this first episode, which opens in a set representing the offices of Scrooge and Marley, before moving into the street for the door-knocker scene, and finally into Scrooge’s rooms.

This is, fairly

obviously, an abridged version of the story, but Grace’s script keeps almost

all of the most famous and familiar elements – with perhaps one curious

exception. She chooses not to include the “surplus population” line, which

seems a strange decision given that it is perhaps one of the most famous in the

whole story. Perhaps she simply thought that it was too grim for younger

viewers, although this seems unlikely given that equally grim elements are

kept.

Birbeck’s

illustrations are also good at representing little nooks and crannies of the

narrative – so, for example, over the passage relating people’s reactions to

Scrooge in the street, such as blind men’s dogs pulling their owners away from

him, we see an example of his in the particular illustration for that sequence.

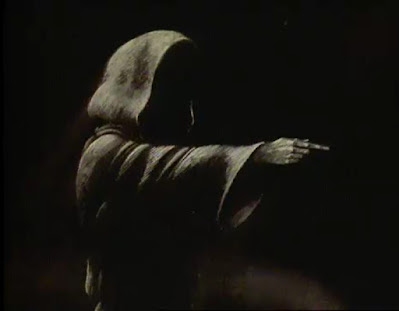

There are some

nice moments where Birbeck’s illustrations aren’t always full-frame, and are

mixed in with Bryant – for example, when Marley appears to Scrooge, and we have

the ghost on one side of the screen and Bryant on the other.

Bryant doesn’t so much seem to represent Dickens as much as a generic Victorian gentleman and general omniscient narrator, although he does so from locations representing where Scrooge is at different parts of the story. This is most evident in this first episode, which opens in a set representing the offices of Scrooge and Marley, before moving into the street for the door-knocker scene, and finally into Scrooge’s rooms.

Past:

Given that Bryant is reading Dickens’s description of the Ghost of Christmas Past from the book, with its strange old-young appearance, Birbeck has a bit of a job on his hands to attempt to realise that, but he does a pretty good job, I think.

Given that Bryant is reading Dickens’s description of the Ghost of Christmas Past from the book, with its strange old-young appearance, Birbeck has a bit of a job on his hands to attempt to realise that, but he does a pretty good job, I think.

There’s only one

set for this episode, Bryant remaining on the Scrooge’s rooms set as he does

for both this and the third episode. We get all the main points of these

visions – the school, the Fezziwigs’ party, and both Belle scenes.

|

| Mr Fezziwig's fiddler! |

Present:

The Ghost of Christmas Present is rendered by Birbeck not just as big and cheerful, but with a hell of a belly on him, too. We have the scene of he and Scrooge out and about in the streets – including the part about people having to take their Christmas meat to be cooked at the baker, which is usually forgotten – and the main visits to the Cratchits’ and to Fred’s house, although the latter is rather cut down in favour of the former.

The Ghost of Christmas Present is rendered by Birbeck not just as big and cheerful, but with a hell of a belly on him, too. We have the scene of he and Scrooge out and about in the streets – including the part about people having to take their Christmas meat to be cooked at the baker, which is usually forgotten – and the main visits to the Cratchits’ and to Fred’s house, although the latter is rather cut down in favour of the former.

Tiny Tim, it must

be said, does actually look somewhat less-than-tiny in the illustration of him

being carried into he house on his father’s shoulders. But Birbeck more than

makes up for that with a suitably haunted-looking depiction of Ignorance and

Want beneath the Spirit’s robes

Yet to Come:

There’s a bit more adjustment in where Bryant reads from here, as we have a graveyard set for much of Scrooge’s encounter with the Spirit. Again, there are all the usual visions of the future, with the Cratchits mourning Tiny Tim being cut down rather. Although I do have to admit, I’m not entirely sure it does that scene any harm, and Grace does retain that section’s best line, about remembering the first parting among them.

There’s a bit more adjustment in where Bryant reads from here, as we have a graveyard set for much of Scrooge’s encounter with the Spirit. Again, there are all the usual visions of the future, with the Cratchits mourning Tiny Tim being cut down rather. Although I do have to admit, I’m not entirely sure it does that scene any harm, and Grace does retain that section’s best line, about remembering the first parting among them.

This is all part of the same fourth and final episode as the Yet to Come section, and for the finale Bryant is back in the set for Scrooge’s rooms, but made to seem much brighter and more cheerful by the change to daylight coming through the windows. Plus a Christmas tree, which Bryant lights some candles on at the end.

Review:

I don’t remember always watching Jackanory when I was a child, but I certainly did sometimes, and there are some of its late 80s and early 90s readings which stuck in my young mind – Rik Mayall doing George’s Marvellous Medicine and Sylvester McCoy doing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in particular.

I can well

imagine this version of the Carol being a fond memory for many children

who watched it in Christmas week of 1982. While it’s obviously just a performed

reading rather than a full-on adaptation, such things can work very well when

done with effort and care – as this is. Bryant is an engaging narrator with a

rich and warm voice and a perfect tone for telling the story. It’s also been

very sensitively adapted, and would be an excellent introduction to the book –

as I expect it was for many younger viewers.

Birbeck’s

illustrations are also, apart from the above-mentioned not-so-Tiny Tim,

excellent. He isn’t tempted to try and ape John Leech’s style, and gives it a

distinctive look and feel of his own.

In a nutshell:

A reading rather than a dramatisation, so not to everyone’s tase. But if you don’t mind that, this is a fine little retelling of the tale, in the best Jackanory tradition.

Links:

BBC Genome (episode 1)

British Film Institute

I don’t remember always watching Jackanory when I was a child, but I certainly did sometimes, and there are some of its late 80s and early 90s readings which stuck in my young mind – Rik Mayall doing George’s Marvellous Medicine and Sylvester McCoy doing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in particular.

A reading rather than a dramatisation, so not to everyone’s tase. But if you don’t mind that, this is a fine little retelling of the tale, in the best Jackanory tradition.

BBC Genome (episode 1)

British Film Institute

No comments:

Post a Comment